This post has been translated from Dutch into English with DeepL. It will be manually edited and streamlined soon.

THE IMAGE of the hexagram: below is Water, above is Wind. Wind blowing across the surface of the water. It creates ripples, waves, wave patterns and currents. Wind and Water carry heat and cold, dust and sand, smells and seeds. Without the movement of Wind and Water, there would be no exchange and dispersion.

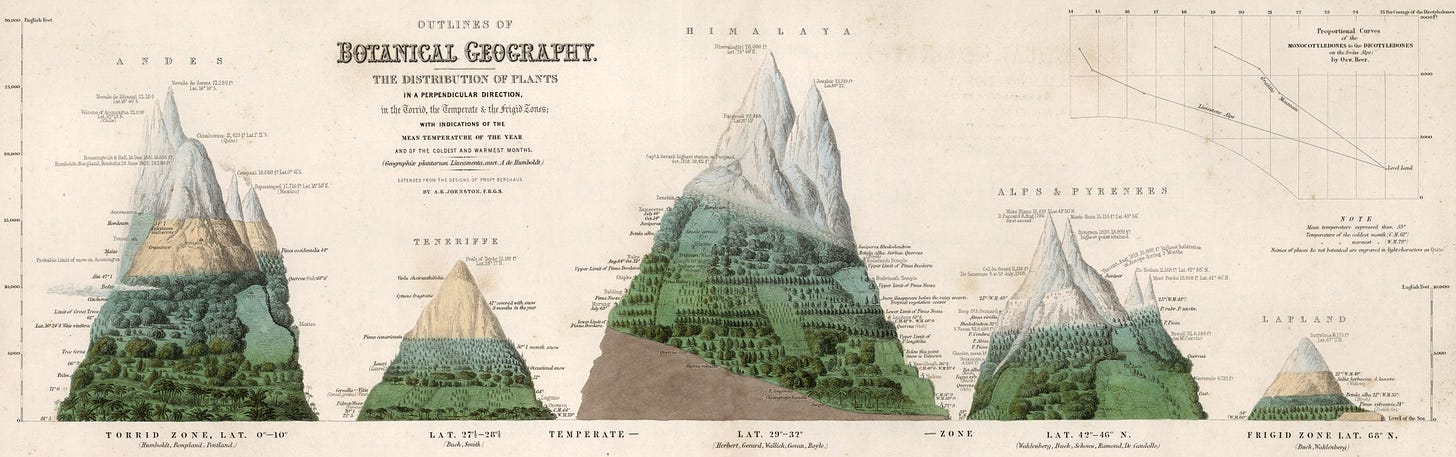

For a plant species that thrives in the valley, the altitude of the mountains can be intolerable. The nights are too cold, the sun unmerciful, and for the pampered valley dweller, the soil is too stony, too dry and too poor. Each altitude has its specific green inhabitants and forms a boundary of habitat. Moreover, mountains form a barrier to seed dispersal. Only after long evolution can plants adapt to different environments and conditions and overcome the obstacle of mountains.

Mountains, along with the great waters of river and sea, are determinants of plant dispersal. Their slopes show a gradual transition of vegetation: from lush green to tough survivors, from tall deciduous trees to stocky conifers, from vegetation with moisture and shade to a world reserved for lichens and grasses. At the highest mountains, the summit is bare, no plant holds out there, there is snow and ice.

Those who climb the mountain from the valley see a change in plant communities comparable to the gradual transition of vegetation from tropical towards polar regions. Enlightenment scientist and adventurer Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) was the first to directly relate horizontal and vertical plant distribution. In the map below, he illustrated the vertical transitions of plant communities from specific peaks depicted in six mountain regions: Andes, Tenerife, Himalayas, Alps, Pyrenees, Lapland.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Acht is meer dan Duizend to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.